The Canadian Museum for Human Rights is a political project

Written by: Ivan Byard, YCL-LJC member in Toronto

The Canadian Museum for Human Rights (CMHR) is once again embroiled in scandal, as yet another probe of workplace harassment has engulfed the museum. This, however, should come as no surprise — the CMHR, from the moment of its conception, has always been a hotbed of ironic ignorance of human rights and the furthering of bourgeois class interests.

The Canadian Museum for Human Rights (CMHR) is once again embroiled in scandal, as yet another probe of workplace harassment has engulfed the museum. This, however, should come as no surprise — the CMHR, from the moment of its conception, has always been a hotbed of ironic ignorance of human rights and the furthering of bourgeois class interests.

The CMHR was conceived in 2003 as a private venture by self-styled libertarian media mogul Israel “Izzy” Asper. Izzy Asper was the founder and owner of the CanWest media empire, and at the time of his death he owned more than a dozen television stations and over 100 newspapers including the National Post. In the early aughts, CanWest was the largest multi-media news, information, and entertainment content provider in Canada. CanWest was, at the time of Izzy’s death, the country’s most profitable television network and one of the world’s largest broadcasting operations with TV stations in Australia, Chile, Ireland, New Zealand, and elsewhere.

The October 1973 war prompted Asper to help found the Canadian-Israel-Committee, becoming the largest pro-Israel lobby of the day, and to use his numerous media outlets to build institutional support for the Zionist project. A 2001 Haaretz article stated, “As Canada’s biggest press baron, [Asper] has raised a ruckus by reportedly ordering his editors to go easy on the Jewish state”.

In 2002, 77 journalists from the Asper-owned Montreal Gazette went on strike and wrote the strike paper Media Giant Silences Local Voices: Canadian Journalism Under Attack. Veteran Montreal Gazette reporter Bill Marsden said at the time “[Asper] does not want any criticism of Israel. We do not run in our newspaper op-ed pieces that express criticism of Israel and what it is doing”.

The CMHR was spearheaded by Izzy Asper’s funding and political will to be used as another platform, just like his media chain, to promote his laissez-faire “anti-welfare state” and pro-Zionist, Likudite views.

The Liberal government under Jean Chretien was an early supporter of the CMHR. As Asper put it in 2003, “Every time this thing got turned back by some department because it didn’t meet this or it didn’t meet that, the Prime Minister [Chretien] simply said to the ministers: ‘Go find a way.’” Asper and Chretien were longtime close friends, and Asper even fired the publisher of the CanWest-owned Ottawa Citizen in 2002 for printing an article critical of Chretien.

In 2006, Charlie Coffey, a Royal Bank vice president and the chair of the CMHR advisory council, said, “We’re doing something almost in reverse, where the private sector is driving something, [although] the plan all along was to have a classic private-public partnership with funding from both sectors”.

During the 2006 Canadian federal election campaign, CanWest’s vice president of regulatory affairs, Charlotte Bell, helped organize a $250-a-plate dinner for soon-to-be Heritage Minister Bev Oda. Minister Oda first began to work for CanWest-owned Global TV in 1979 as a producer. In 1987, Oda left Global for an appointment as a full-time commissioner of the Canadian Radio-Television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC) for a seven-year term. As a commissioner, she led the deregulation of Canadian television and radio. After Oda’s term ended, she was welcomed back to the private sector with a promotion to an executive position, joining Baton Broadcasting as Senior Vice President of Programming, and in 1998 was further appointed Senior Vice President of Industry Affairs for CTV Inc.

As Heritage Minister, Oda oversaw the Tory government’s shift in its relationship with the CMHR, from an initial investment of $30 million from the Chretien Liberal government in 2003, to the CMHR’s designation as a federal museum with project costs reaching well into the hundreds of millions of dollars and expected operating costs over twelve million dollars annually, all overseen by the Asper family-dominated board. Minister Oda resigned in 2012 after it was revealed during a conference on immunization of poor children in London, England that Oda had refused to stay in the accommodations provided by hosts. Instead, Minister Oda used public funds to stay at the luxury, Fairmont-managed Savoy Hotel, in a non-smoking room she was billed for smoking in, with a private limousine to chauffeur her between the convention and the Savoy.

After the Tory win in the 2006 federal election, CanWest named Derek Burney as its chairman, filling the vacancy created by Izzy Asper’s death in 2003. Burney had just finished his role leading Harper’s transition team to power after the election. Burney was Conservative Prime Minister Brian Mulroney’s chief of staff and later his ambassador to the U.S. from 1989 to 1993.

The following year, Conservative Prime Minister Stephen Harper announced that the federal government would assume responsibility for Izzy Asper’s personal project. This made the CMHR the first federal museum outside of Ottawa and the first federal museum established in over forty years. Further, the section of Waterfront Drive that the CMHR is located on was renamed “Israel Asper Way”. The museum’s first CEO, Stuart Murray, was the former leader of the Conservative party in Manitoba.

Karen Busby, a University of Manitoba law professor and co-author of The Idea of a Human Rights Museum, a book examining the foundation and political context of the CMHR, said of CMHR CEO Murray, “He had never even been on the board of governors of a museum, didn’t know anything about human rights… But he was appointed as the CEO in order to keep a political check on the museum.”

From its beginnings, the CMHR was criticized for its chauvinistic approach to Indigenous history, foreshadowing struggles to come. The site of the CMHR was built at the Forks, where the Red River meets the Assiniboine River. The Forks has been home to First Nations for at least 6000 years. Almost 600,000 artifacts were recovered during a year-long archaeological dig at the site, yet only two percent of the fill removed was sifted. ″(It was) the worst case of legal destruction of the rich heritage that I have had the misfortune to witness,” said Leigh Syms, a former archeology curator at the nearby Manitoba Museum, in Busby’s The Idea of a Human Rights Museum.

Before the CMHR could even open its doors, it was facing mass staff resignations over political interference. In 2012, 38 employees left the CMHR over political interference from the federal Conservatives. Stuart Murray, then-CMHR CEO, said regarding the mass exodus of employees, “I cannot afford to carry any staff member who is not 100 percent committed to this project”. The trailblazing lawyer and scholar Mary Eberts was one of the museum’s most prominent resignations of 2012. In an open letter, Eberts said the CMHR would not be able to meet its mandate for being independent from the government due to the domination of political figures on the board and donor list. Eric Hughes, then-chair of the museum’s board of trustees and an Alberta oil industry executive, countered, “I think if you look at the overall suite of galleries within this museum, I think we have overachieved, sometimes, the critical stories.” Hughes’ insistence over how the museum would treat issues such as the history of “human rights in Canada” and the ignorance of factors such as poverty, capitalism, and climate change led to further resignations and claims of political interference.

The board of the CMHR wrote a letter to management in 2014 before its official opening calling for material changes to be made to the visitor experience to maintain a “positive, optimistic tone”. “People said the [atrocities] gallery felt like a little shop of horrors,” Angela Cassie, then CMHR spokesperson said at the time. She added, “Departed staff who had scholarly or academic backgrounds may not have understood what prospective museum patrons desire in terms of content and presentation.” Then-CEO Murray boldly added, “I’m not a human rights expert and have never pretended to be, [but] this is going to be a museum for human rights, not human wrongs”.

To coincide with International Women’s Day in 2014, the CMHR asked Veronica Strong-Boag, the former president of the Canadian Historical Association, to write a blog post in her area of expertise, that being the history of women and children in Canada. The post appeared on March 4, 2014, but was removed hours later after museum staff deemed a passage criticizing the federal Conservative government unacceptable. The blog post particularly noted that the Conservatives have had an “anti-woman record”. Strong-Boag said CMHR staff first asked her to back up the claim, but ultimately rejected a revised blog posting with further citations as a “political statement”. Strong-Boag characterized the museum’s decision as an act of censorship. “This isn’t a question of academic freedom, it’s a question of what we think we are wanting for our blog posts,” said Maureen Fitzhenry, then-CMHR media-relations manager. “We will more clearly ask that guest blogs consist of anecdotal accounts of first-person experiences that illuminate human rights themes. We also make efforts to ensure that guest blogs not be used as a platform for political positions,” wrote CMHR spokesperson Angela Cassie in a statement. In a response letter, Strong-Boag called Cassie’s statement “naive and pedagogically unsound” for a museum “supposedly dedicated” to promoting human rights. “It suggests that human rights are almost purely about entertainment and that authors can pretend impartiality in dealing with them” Strong-Boag wrote.

David Asper, one of Izzy Asper’s two sons, said he takes these criticisms of the museum personally. “It feels like an attack on my father, my family, and my own integrity.”

The yet-to-open CHMR has been criticised for avoiding the use of the term “genocide” to describe the attrocities perpetrated against Indigenous Peoples in Canada. A year before the CMHR opened, CMHR spokesperson Angela Cassie said, “We are not a court. We are not an academic institution. We rely on those sources for information to inform our exhibits”.

The CMHR changed their policy in 2019, finally recognizing the treatment of Indigenous Peoples in Canada as genocide. “I think now what’s happened is we understand it’s not just our role, but our responsibility and our commitment as a national institution that’s dedicated to human rights education,” said Louise Waldman, the museum’s Marketing and Communications Manager. The decision of the CMHR came an entire four years after the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) released its final report in 2015, officially declaring the acts of the residential school system as cultural genocide. Questioned in 2015 after the release of the TRC report whether the CMHR would formally use the term “genocide” in its residential school system displays, CHMR officials said it would depend on if the federal government recognized “genocide” as a legitimate description.

Protest at the opening ceremony of the Canadian Museum for Human Rights

In September 2014, the opening of the CMHR was picketed to raise awareness of the demand for an inquiry into murdered and missing Indigenous women and girls, First Nations water rights, and the Palestinain struggle for self-determination. Music group A Tribe Called Red was initially set to perform at the museum’s opening ceremony but boycotted the event after consulting with local Indigenous organizations.

The Manitoba Métis Federation voted to boycott the CMHR in 2014 over censorship. The CMHR approached the Federation to ask which Métis performers should be included in the opening ceremonies. The Federation’s choice — decorated Métis musician Ray St. Germain — was rejected, and a spokesperson for the CMHR said, “[the museum] had to ensure the opening ceremonies reflected all of Canada”.

Stewart Redsky, a former Chief of Shoal Lake Band 40 Ojibwa First Nation, wrote a letter in 2007 to Antoine Predock, the American architect of the CMHR. The letter advised that the lives and livelihoods of community members have continually been put at risk by Canada’s expropriation of their land and the resulting artificial isolation. Chief Erwin Redsky wrote a further open letter in 2014 after there had been no response to their previous correspondence. Erwin Redsky noted the deeply insulting hypocrisy of the promotional campaign for the CMHR that presented the building as “honouring the First Nation relationship with water” with the so-called “healing properties” of the reflecting pools in its design. Shoal Lake 40 was turned into a man made island more than a century ago so that water from their lake could be directed to the burgeoning City of Winnipeg. The aqueduct constructed to provide Winnipeg with water was built on the First Nation’s old burial grounds. Today, the people of Shoal Lake 40 are under a 23-year-long boil water advisory, and the water they use to bathe and wash causes rashes. A water treatment plant is now under construction nearby. The resulting forced isolation of the man-made island has made life more difficult and dangerous, with many people having fallen through the ice on Shoal Lake. The first all-season road to the community only opened in 2019, more than a century after the man-made canal cut off the community to supply Winnipeg with water. Before the completion of construction on the all-season road, the community was without access to the mainland during the spring and fall. This created significant hardship, often resulting in serious health incidents and even death. To complete their schooling, students from Shoal Lake 40 have to leave the community to be placed in boarding homes for their entire high school career.

Graffiti on the Canadian Museum of Human Rights, February 2020 (ph: @CMHR_News)

In February 2020, during the height of solidarity actions against the armed Canadian invasion of Wet’suwet’en territory to construct the Liberal and New Democrat Party Coastal GasLink, the entrance of the CMHR was marked with red spray paint asking “IS THIS THE FUTURE YOU WANT” and demanding “LAND BACK”. Then-CMHR CEO John Young said, “to be honest, my first instinct was a little of blood boils.” The CMHR contacted police and handed over security footage, and later that month an 18 year old Winnipeg man was arrested and charged in connection with the solidarity action. The CMHR hypocritically highlighted the event in their annual report as an accomplishment and “opportunity for dialogue”:

“While the Museum did not condone the use of graffiti, its leaders chose to treat this incident as an opportunity for genuine dialogue. Museum CEO John Young called an impromptu news conference and the Museum asked this question on its social media channels.The resulting national media coverage hit newspapers and airwaves for days. And an outpouring of online responses resulted in one of the most highly engaged social media posts in the Museum’s history, reaching over 200,000 people across all platforms. This success was an encouraging result of Museum efforts to generate positive media attention on human rights issues and create a digital space where ideas can be shared and different perspectives understood.”

There have been complaints that the CMHR has given primacy to the Holocaust over other historical atrocities. The program of the CMHR is centered around the permanent exhibit “Broken Glass Theatre” which uses glass shards to evoke Kristallnacht, and invites a comparison of all genocides to that of the Nazis. The CMHR uses the Holocaust as an archetypal example of genocide in a ‘failed democracy’, with the implicit warning that this could happen again, even in Canada. Izzy Asper was inspired to create the CMHR by the state-sponsored United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. At first, Asper’s vision was of a museum of tolerance, similar to that in Los Angeles, in which the Holocaust would play a central role. In fact, regarding complaints of ignorance of local Canadian human rights atrocities, Gail Asper stated, “We never ever set out to build the Canadian Museum for Human Rights… that was not the mission”. The CMHR has said that it decided to feature the Holocaust for a number of reasons, including the fact it was the catalyst that prompted the world to forge a legal framework for the development of international human rights law, specifically the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the United Nations Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide.

However, some of these complaints about the central role of the Holocaust have come in the form of antisemitic propaganda and racist campaigns. The Ukrainian Canadian Civil Liberties Association (UCCLA) started a campaign in 2010 against the proposed content of the CMHR. The UCCLA took out a full page ad in the Hill Times newspaper and sent out postcards depicting Jewish backers of the prominent Holocaust gallery in the CMHR as pigs. This hate propaganda featured an illustration from the 1947 Ukrainian edition of George Orwell’s novel Animal Farm, which depicts a fat pig with a bullwhip overseeing an emaciated horse dragging a wagon. Prof. Per Anders Rudling, a scholar of Eastern European history, specializing in nationalism antisemitism in Ukraine, said that, “the argument of [the alleged domination of] Jewish Communists is a staple in Ukrainian nationalist rhetoric and has led to protests from non-nationalist scholars”. The UCCLA also lobbied to have the Holodomor (the idea that the 1932-1933 famine, arising from crop failures during the social upheaval of Soviet attempts to collectivize and modernize agriculture, was a deliberate genocide of the Ukrainian people — a theory which, according to historical evidence and the work of numerous scholars, originated in Nazi propaganda) get equal billing with the Holocaust. Under the proposed plan, the Holodomor was to have a permanent display in the “Mass Atrocities” section of the museum.

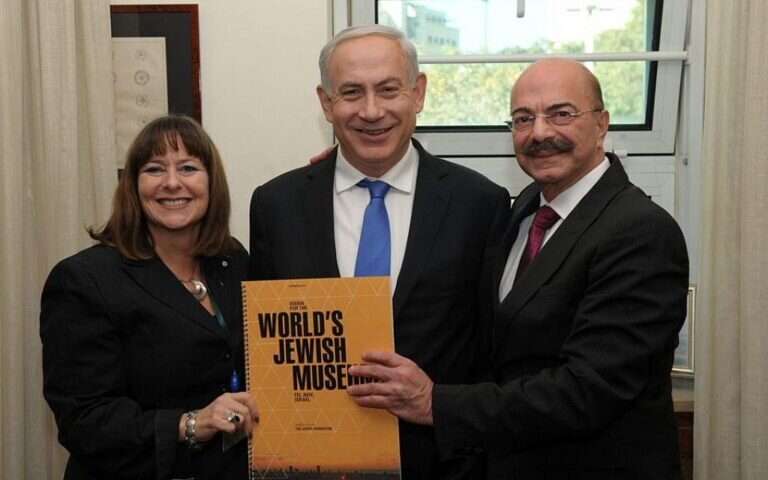

Izzy Asper, Gail Asper, and Benjamin Netanyahu at an event in 2002 (ph: Times of Israel)

In 2002, the Asper Foundation co-hosted a four-city speaking tour in Canada by current Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, who then served as Minister of Foreign Affairs of Israel. After window-smashing protesters disrupted Netanyahu’s speech at Montreal’s Concordia University, ending the event, Asper accused them of Nazi tactics: “The minority of a rabble, a rioting group of essentially thugs and lawbreakers, employed the techniques introduced 70 years ago by Adolf Hitler and his Brown Shirts.” Within months, Asper’s CanWest Global made a film titled “Confrontation at Concordia” comparing window-smashing at Concordia to the events of Kristallnacht which led to nearly 100 deaths and the mass-destruction of Jewish synagogues and buildings.

Currently, the Asper Foundation is working with fundraisers to solicit donations for “The World’s Jewish Museum”, a $400 million proposed museum in Tel Aviv, intended as a gift from the Aspers to Israelis on their country’s 75th birthday in 2023. Gail Asper envisions the project as a “Jewish Hall of Fame” to celebrate the achievement of a number of individuals. She came up with the idea after lamenting that Jerusalem’s Israel Museum and the Museum of the Jewish People in Tel Aviv told the “anthropological story of Jews around the world not as individuals, and not relating to values or honouring achievement”.

This $400 million project is concerning when, for seven years, a $70 million discrepancy in assessed value of CMHR land between the city of Winnipeg and Federal Government created budget shortfalls for the city. The city of Winnipeg had assessed the museum building at approximately $100 million, while the Federal Government has pegged its value at around $30 million. The actual cost of the CMHR was over $350 million by the time it opened in 2014. The Federal Government is exempt from paying taxes to provincial or municipal governments taxes, instead making “payment in lieu of taxes”. This dispute was finally resolved in 2017, only after years of municipal social services taking a hit from this joint CMHR-Federal Government tax evasion.

The Public Service Alliance of Canada (PSAC), the union representing 160 members employed at the CMHR, has raised concern over the museum’s ongoing and systemic racism, sexual harassment, and discrimination, as well as being censored and pushed out of their jobs with CMHR management since at least October 2018. In May 2020, the union made proposals in contract talks with the museum to ensure anti-harassment training for all museum staff – including management – however, these proposals were rejected by the CMHR. PSAC filed grievances over the lack of anti-harassment training and issues related to discrimination in the workplace.

Five current and former female employees at the Canadian Museum for Human Rights allege that they have been sexually harassed by the same male colleague, and say that their complaints to human resources were dismissed. After the women complained about this colleague formally to the museum’s HR department, he was put on paid leave and the museum hired an outside law firm to probe his conduct. He was then allowed to return to work after a lawyer concluded the allegations were just rumours in the workplace and the women were “bullying” the man. CBC News reported that the man, who had worked with visitors at the CMHR in Winnipeg since 2016, as well as his direct supervisor resigned in August 2020. The CMHR had on one other occasion hired an external law firm to probe sexual harassment allegations but that investigation did not involve the same employee. The CMHR said it followed all recommendations made in both instances.

In the wake of the deaths of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and D’Andre Campbell at the hands of police, a peaceful protest took place in Winnipeg on June 5, 2020. The protestors marched from the Manitoba Legislative Building to the Canadian Museum for Human Rights. The following day, the CMHR posted images and expressions of support for Black lives on social media. This sparked outrage from current and former workers at the CMHR. A campaign called #CMHRStopLying shared firsthand accounts of discrimination and systemic anti-Black and anti-Indigenous racism. This campaign grew to also include reports from former employees’ experiences with homophobia, with workers revealing that they were forced by CMHR management to censor content about the struggle for 2SLGBTQ rights as well as “women’s content like abortion and pregnacy”. Workers at the CMHR were further told not to mention anything related to the empowerment of women, like the story of civil rights pioneer Viola Desmond.

An independent external investigation of the CMHR released its findings in August 2020, stating:

“Racism is pervasive and systemic within the institution, with significant impacts on hiring and retention of BIPOC employees and harm to individuals resulting therefrom … At the present time, there is no finding as to whether sexual harassment investigations were undertaken improperly or at all prior to the fall of 2016. There are indications that sexual harassment and stalking complaints made by Black women may not have been investigated or addressed adequately prior to the fall of 2016. There are no indications that sexual harassment complaints are not being investigated or addressed adequately at the present time … Black, Indigenous and People of Colour have been adversely impacted physically, emotionally and financially by their experiences within the (CMHR).”

Because of these allegations, the CMHR has seen a crisis in not only general museum employment, but management as well. John Scott, the former CEO of the CMHR, announced in June 2020 he would not seek reappointment from the board in August following calls from the Public Service Alliance of Canada for his resignation. However, the board announced his immediate departure in June. In addition, the CMHR has paid out more than $309,000 in severance this year — the highest amount the CMHR has paid out since opening in 2014. Previous highs were: $121,648 (2018); $83,884.13 (2019); $12,032.11 (2014); $3,097.55 (2015); $6,301.36 (2016). This amount is much higher than publicly-disclosed severance payouts at other federal museums. In comparison to the other 8 federal museums, three have not paid out anything in 2020, while four others refused to provide the information. The Canadian Museum of Nature paid $7,000 in severance in the 2018-2019 fiscal year. CMHR spokesperson Maureen Fitzhenry said that from June 18 to August 26, nine people left their employment at the CMHR, including three who were in a management or executive role. By comparison, in the same time period last year, Fitzhenry said, there were 12 departures but none were in management.

Pearl Eliadis, a human rights lawyer, educator, and author, wrote in August 2020, “I served as an external adviser and peer reviewer for the museum over several years. The current crisis may be shocking, but it’s a predictable consequence of the museum’s history of separating strategic management practices from human rights principles”.

The findings of the external report from August 2020 also point to a divisions between management practices from human rights principles:

“Staff who interacted with the public and developed programs was that ‘front-facing’ or ‘front-of-house’ employees generally had backgrounds and/or strong interests in human rights, whereas most individuals in management did not.

In the view of many current and former staff members interviewed, there was a tendency on the part of management to treat the Museum as a profit-oriented corporation having its primary focus on revenue generation to the exclusion of organizational health and the fulfilment of its mandate.”

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) is the cornerstone of international law. After the victory over facism, representatives from all regions of the world drafted a common standard, for the first time, so that fundamental human rights could be universally protected. The UDHR was a tremendous achievement for the workers of the world. The UDHR laid out that everyone has the right to: employment; an education; rest and leisure; a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of themselves and of their family, including food, clothing, housing and medical care and necessary social services, and security in the event of unemployment, sickness, disability, widowhood, old age, or other lack of livelihood in circumstances beyond their control. The opening preamble of the UDHR states, “recognition of the inherent dignity and of the equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family is the foundation of freedom, justice, and peace in the world”. It is important to recognize that the struggle for human rights is ongoing. The enforcement of rights is thus something that is fought for, and part of that fight includes education and celebration. But with the CMHR we have to ask, whose class interests are being projected?

In the Manifesto of the Communist Party, Marx and Engels laid out, “The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles … society as a whole is more and more splitting up into two great hostile camps, into two great classes directly facing each other — Bourgeoisie and Proletariat.” In a bourgeois state like Canada with its state-monopoly capitalism, the monstrous oppression of the working people by the state merged with the all-powerful capitalist associations, so called public-private partnerships like the CMHR, use the state to extract capital from the masses and hand it over to the bourgeois class like the Asper family. The CMHR was always intended as a class project, promoting the interests of the ruling class.

Izzy Asper’s media empire was an example of state-monopoly capitalism in action. Izzy benefited from deregulation and laissez-faire rulings to accumulate his capital. His stations in Canada technically were not a network — he was not required to invest in Canadian content, instead specializing in programming inexpensive re-runs of US shows. In 2000, Communications, Energy and Paperworkers Union vice president Gail Lem said Asper’s holdings constituted “an unprecedented and horrifying level of concentration of ownership in the Canadian news media.” A Globe & Mail obituary for Izzy called him “the country’s biggest insider: the most powerful media baron… with a pipeline to the political leadership of the country.”

Izzy had a net worth approaching $2 billion inherited by his trustafarian failchildren who would go to drive Izzy’s empire and the largest media company in Canada into bankruptcy just 6 years after Izzy died. But, this was not before they could make huge contributions to right-wing political parties, run unedited thinktank content from places like the notorious Fraser Institute, and egregiously edit wire services in accordance with a CanWest policy to label certain groups as “terrorists” pushing their political agenda.

A study released in 2006 found that the Asper family-controlled National Post was 83.3 times more likely to report an Israeli child’s death than a Palestinian child’s death in its news articles’ headlines or first paragraphs. In 2008, CanWest launched a lawsuit against the Palestine Media Collective for producing a newspaper parody of The Vancouver Sun that satirized this bias. That media companies like those of the Asper family can run amok — completely unchecked and oftentimes supported — in Canada shows a glaring failure of the Government of Canada to enforce human rights.

The United Nations Human Rights Council outlined the failure and absence of human rights enforcement in Canada with the 2018 Universal Periodic Review (UPR). Numerous references were made to the Canadian state’s failure to sign, ratify, or implement numerous international treaties, notably: the International Human Rights Instruments, including the International Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment; the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance; the International Conventionon the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families; the International Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities; the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights; United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights; the Safe Schools Declaration and the Guidelines for Protecting Schools and Universities from Military Use during Armed Conflict; United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination Guidlines; American Convention on Human Rights (1969); the Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention, 1989 (No.169) of the International Labour Organization (ILO); and the Universal Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

The 2018 UPR of Canada made 275 recommendations for the protection and enforcement of human rights in Canada. The most repeated and emphasised areas were:

Interpreting the Charter of Rights and Freedoms to confirm the interdependence and indivisibility of all human rights with a view to ensuring access to food, health and adequate housing for all those living in the country;

ending the housing crisis;

ensuring all children have equal access to government services such as health, education, and welfare, and address the disparities in access to these services for Indigenous children in particular; cease cases of children being taken away from their parents by child welfare agencies and implementation of Jordan’s Principle;

improving gender equality with a view to enhancing women’s participation in decision-making, full-time employment and equal pay for equal work equal; safe access to abortion and comprehensive sexuality education;

preventative measures to stop violence against women and girls, with an emphasis on Indigenous women and girls;

ending the forced sterilization of women from vulnerable groups and punish those responsible and assist affected women;

people-and community-centred mental health services that do not lead to institutionalization, over-medicalization or practices that do not respect the rights, will and preferences of all persons;

Strengthen measures to combat structural discrimination against Black Canadians, Indigenous peoples, 2SLGBTQI people, and religious minorities;

establishing effective mechanisms of investigation and punishment of perpetrators of acts of discrimination and violence against them such as introducing legislation to ban any organization that incites discrimination, particularly anti-Black, Islamophobic, antisemitic, anti-Indigenous, and anti-migrants and refugees, and criminalize acts of violence perpetrated on that basis;

ending the trafficking of persons;

Combat racist hate crimes and racial profiling by the police, security agencies and border agents. End the practices of solitary confinement of prisoners, the excessive use of force, the high number of deaths involving the police among vulnerable people, arbitrary detentions and reduce overcrowding in detention centres;

prevent human rights impacts by Canadian companies operating overseas, as well as ensuring access to remedies for people affected, and share Canada’s practices as appropriate mining, oil and gas companies. Make the Office of the Extractive Sector Corporate Social Responsibility Counsellor an independent body.

The most glaring hypocrisy of all regarding the CMHR is that its phallic, 100-metre “Izzy Asper Tower of Hope” (he insisted that the winning architecture design would have to have a tower) is in the middle of a city where pernicious poverty and failures of public policy strip human rights protections away. The CMHR lies on the bank of the Red River that rivals BC’s Highway of Tears for being synonymous with murdered and missing Indigenous women and girls. A December 2020 report from the Planning Council of Winnipeg demonstrated that, if current trends continue, it will take Manitoba more than a thousand years to end child poverty. The report, Manitoba: Poverty Central, is based on 2018 data and reveals that the province once again has the highest rates of child poverty in Canada. It follows up on the Broken Promise Stolen Futures report, which was based on 2017 data. “It is more than time we make poverty the problem and not the people trapped in it. If we truly cared about caring for our most vulnerable, we would not be seeing this disturbing rise in child poverty rates,” said Kate Kehler, the council’s executive director, “We have to remember, this is 2018 data… but how much worse has the 2020 pandemic made it for far too many Manitoba families?” In December 2020, multiple new cases of Trench Fever in Winnipeg, a now-rare illness that commonly afflicted soldiers during the First World War, made international news. Dr. Carl Boodman, after treating four cases this year, wrote in the Canadian Medical Association Journal in December 2020, “It’s an [easily preventable] disease associated with wartime conditions and refugee camps, and it’s found in Canada. If we didn’t have this degree of poverty in Canada, we wouldn’t have this disease.” Aside from the four cases in Winnipeg this year, only four other cases are known to have occurred in Canada since the mid-1990s. Thus we see that the CMHR is a shameful tribute to Izzy Asper, one of the wealthiest Canadians to ever live, by Izzy Asper, paid for by the people, in the heart of Canada’s child poverty capital.

As award winning architectural journalist Adele Weder aptly wrote in a 2014 article in the Walrus:

“The Canadian Museum for Human Rights is a tourist trap, failed memorial, and white elephant … Perhaps it’s no coincidence that the Museum for Human Rights looks a lot like (architect) Predock’s unbuilt 1994 scheme for the Atlantis Hotel and Casino in Las Vegas, only with a more robustly erect tower. Museums are now playlands, built as much to attract paying customers and galvanize donors and local economies as to engage citizens with their content. And many people will be engaged, by compulsion as much as by free will: politicians will make the requisite pilgrimage to the museum, and teachers will shepherd busloads of schoolchildren through it. Don’t expect researchers to flock to it, however; it has just 200 or so original artifacts, and its library is not much bigger than a broom closet … In coming years, as the novelty of a human rights theme park wears off, the pressing question will likely be: What else can we use it for? Repurpose it as the amusement park or resort it already is in design? Or, perhaps more appropriately, rebrand it as the Museum of Human Ego … this behemoth of a venue, itself an architectural testament to public-private megalomania.”

The 56-page long annual report from the CMHR for 2019-20 makes references to “diligent fiscal management”, “corporate performance”, and “expertise in business”, however there are no references to “class”, “poverty”, or “capitalism”, the driving causes of human rights violations. As Marx and Engels wrote in the Manifesto of the Communist Party:

“[Capitalism] has resolved personal worth into exchange value, and in place of the numberless indefeasible chartered freedoms, has set up that single, unconscionable freedom — Free Trade. In one word, for exploitation, veiled by religious and political illusions, it has substituted naked, shameless, direct, brutal exploitation … all that is solid melts into air.”

The CMHR is once again embroiled in scandal. But the fact is that the project was a scandal from the onset. The CMHR was conceived as a legacy political project by Izzy Asper, who used his accumulation of capital to promote both Canadian and Israeli violations of human rights and to censor critics. Why would his vanity weaponization of human rights be operated differently than his media empire, which he governed every aspect down to the minutia to promote his class interests? The CMHR is a political project to help perpetuate political power, the organized power of one class for oppressing another.

Note: This article was originally published in Rebel Youth Magazine.

More Articles